I painted the bouquet of flowers (note the purple irises and the mask) that I bought from Roberts Florals in Highland Park, New Jersey on Purim. My guests enjoyed the bouquet along with the meal. I am relatively pleased with the result of the painting.

My current ultimate goal is to get better at painting portraits. I am confident in my flower painting abilities. I could improve in details, but I do not strive to be a realistic floral artist. One reason I chose to paint the bouquet is it was a good warm up to painting after Shabbat and after a week of little painting in general.

Why I failed miserably at 100 people week

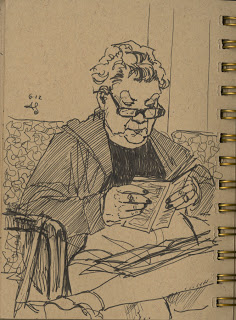

Early in March there was a competition to draw or paint 100 people in a week. My start was delayed by Purim; I had lots of preparations to do for the holiday, and guests showed up to entertain us at our seudah (festive meal). Finally, I went out one day with my sketchpad and doodled quite a few people. I did not care much for the result, so it is not getting posted here. Then I ran out of time to go outside and look for people. So I went up to my attic late one night, and I took down several photos of people that I found inspirational.

How 100 people week Inspired Portraiture Adventures

One of the photos that I found was one of my sons showing a dandelion to a chicken. I did one quick sketch; the proportions of the head were off. I started another. I continued painting into the night, and I am please with the result: gouache media, lots of strokes and movement. I like how the light falls on the figures and the variety of hues established.

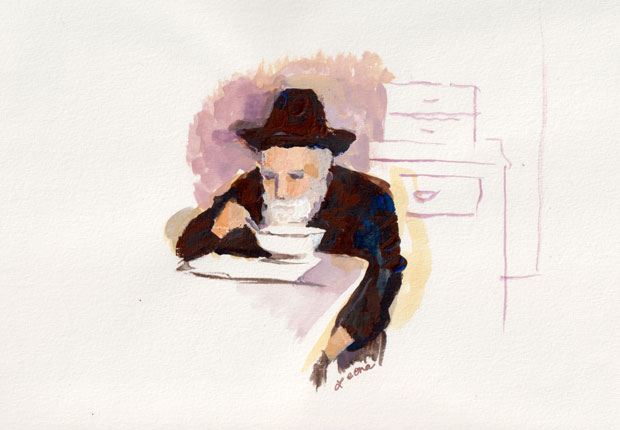

Here is another portrait that I did, from an old black and white photo of a relative eating soup. This portrait is also done with gouache. Maybe I will do another version in the future with more attention to the background.

More Flowers to Show

Whenever I go shopping with a certain friend, I am done long before she is. No problem! Each store seems to have a section of flowers. So I put my paid groceries in the car, and I return to draw with a Uniball pen whatever strikes me in the store. Often, the flowers stand out. Here are a few of my favorites:

This one was painted after another one that had the brand name of a large chain store got rejected from an online shop that sells artists’ goods. Lesson learned: buy local flowers. Advertise local stores. No need to ruffle the feathers of any large chain stores.

I often like painting a palette of colors near my watercolors. This palette compliments the flowers nicely, organic flowers shapes near geometric squares.

More on Painting Flowers

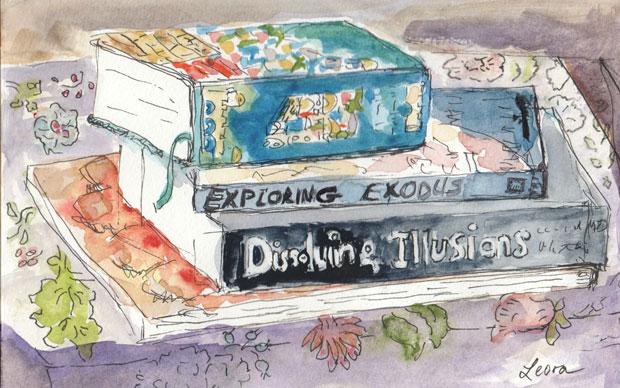

I am reading Painting Flowers in Watercolor with Charles Reid, a classic in the watercolor book world. Two ideas that I look forward to incorporating in future watercolor floral sketches or paintings:

1) Pay attention to negative shapes that the flowers make almost as much as to the flowers themselves. Do not overwork the details. Paint the background along with painting the flowers. The background should not be an after thought.

2) When painting the background, don’t do one solid expanse of one color. Do a variety of color in a mix that compliments whatever flowers one is painting.

Charles Reid uses a lot of cadmiums in his palette (Cadmium Yellow, Cadmium Orange). I will substitute colors in my palette, probably Hansa Yellow (light, medium, or dark) and New Gamboge. One exercise is to paint daffodils. Another is techniques for white flowers. Daffodils and magnolias are in bloom now. Hopefully, I will be able to experiment with his ideas.

It is now the Jewish month of Nissan. In Nissan we celebrate freedom on Passover. We are also commanded to say blessing on a fruit tree when it shows its first blossoms. I will be looking around my neighborhood for all kinds of blossoms for blessings and for sketches.

Welcome to the May Jewish Book Carnival!

About the Jewish Book Carnival:

The Jewish Book Carnival is a monthly event where bloggers who blog about Jewish books can meet, read and comment on each others’ posts. The carnival was started by Heidi Rabinowitz and Marie Cloutier to build community among bloggers and blogs who feature Jewish books.

On her blog, Book Q&As with Deborah Kalb, Deborah interviewed the editors of the new book The Ones Who Remember: Second-Generation Voices of the Holocaust.

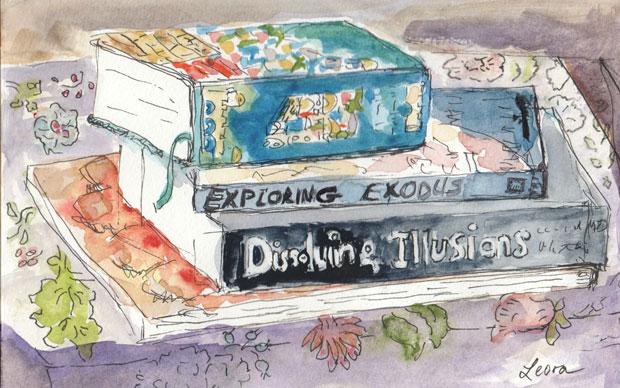

Reuven Chaim Klein reviews four books on his blog The Rachack Review: Disputed Messiahs: Jewish and Christian Messianism in the Ashkenazic World during the Reformation, Moshe Emes: Torah and Science Alignment, Kabbalah and Sex Magic: A Mythical-Ritual Genealogy, and Understanding the Alef-Beis: Insights into the Hebrew Letters and the Methods of Interpreting Them.

Please read Howard Lovy’s interview for Publishers Weekly with Danica Davidson, co-author of I Will Protect You: A True Story of Twins Who Survived Auschwitz: Authors Bring Holocaust Story to Young Readers.

On gilagreenwrites, Gila interviews author Avner Landes about his debut novel Meiselman: the Lean Years.

Why is the Hebrew Bible different from all other Bibles? In April, Jill at Rhapsody in Books reviewed “The Grammar of God” by Aviya Kushner in which Kushner answers this question in a fascinating analysis.

Every day in May, Heidi Rabinowitz will post #JewishAmericanHeritageMonth daily kidlit book recommendations at the Facebook page Book of Life, featuring Jewish books from across the United States.

The Book of Life Podcast’s May episode features an interview with Dayna Lorentz, author of Wayward Creatures, a middle grade contemporary novel told in two voices: a troubled Jewish boy and a wayward coyote.

On her My Machberet blog, Erika Dreifus routinely compiles news of Jewish literary interest. Here’s one recent post, expanded for #JewishAmericanHeritageMonth and other notable May occasions and including a special Yom HaZikaron/Yom HaAtzmaut giveaway that continues through May 18.

At Jewish Books for Kids and More, Barbara Bietz interviews author Betsy R. Rosenthal about her new middle-grade novel, WHEN LIGHTNIN’ STRUCK.

Life Is Like a Library reviews Ayelet Gundar Goshen’s Waking Lions:

A Jewish Grandmother read a couple of young readers on Jewish themes from Kar-Ben Publishing and was happy to be able to give great books to a granddaughter. The Button Box by Bridget Hodder and When Lightnin’ Struck by Betsy R. Rosenthal both have wonderful stories with interesting Jewish themes, They both give some background on Spanish Jewry, which isn’t known by many people.

A Jewish Grandmother also reviewed Dear Cousin a great book with a strong moral message. It’s a very well-written eulogy/memoir by Elchonon Boruch Galbut about his cousin Brian Boruch Tzvi Galbut.

Bubby has been writing a series of posts on World War II and God’s role in Jewish history. The latest is called All the World is a Hidden Purimspiel. The plan is to put the posts together into a book.

Why do art? And how does one get inspiration? For the first question, I will quote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at the end of this post. For the second, I will describe the process of how I created this watercolor.

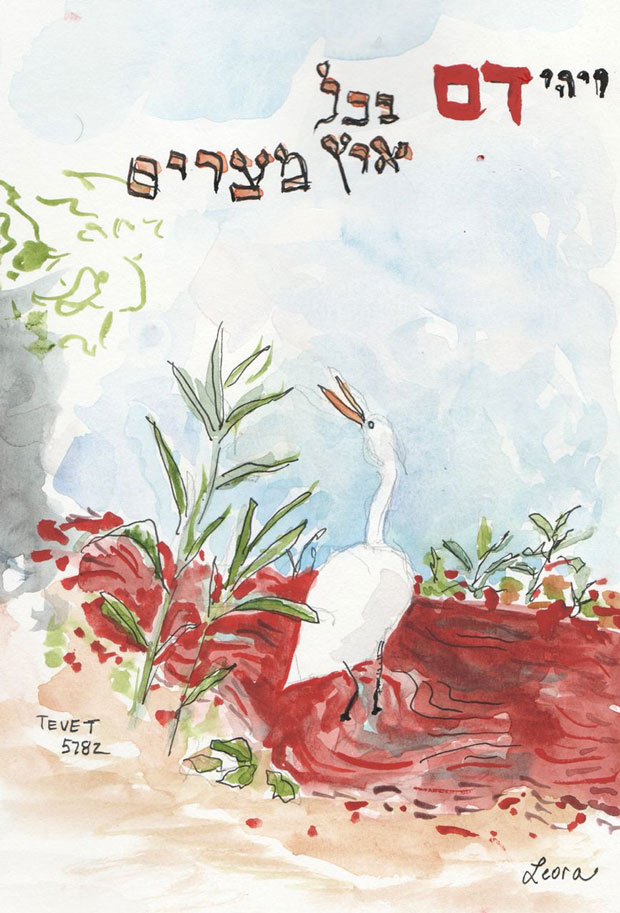

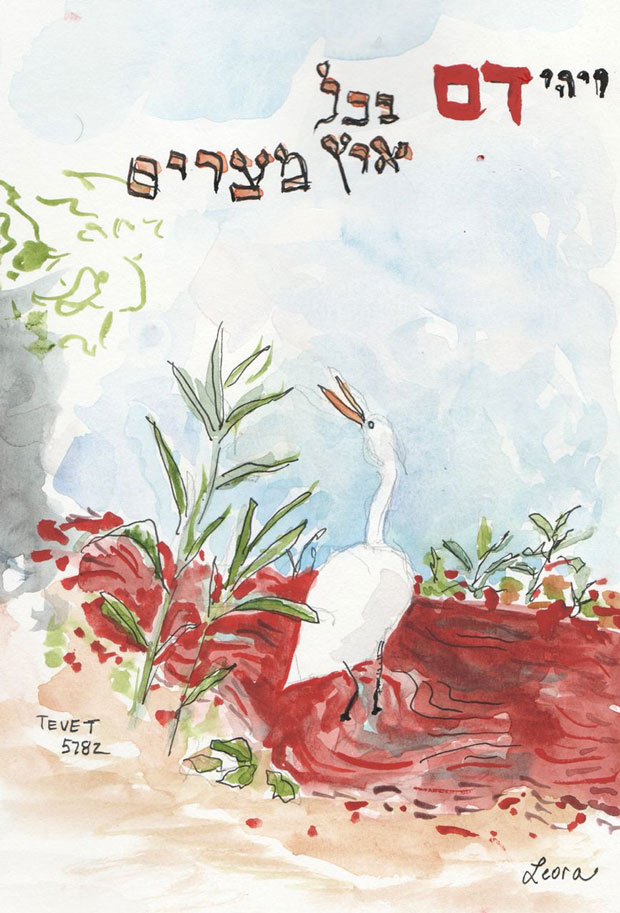

I painted this watercolor in response to reading about Plague Number One: blood. How does one depict a bloody river Nile? A while back, I painted a dull straight river of blood. I wanted something more watery. I looked at paintings of Winslow Homer and J.M.W. Turner. Both are known for their water scenes. I happened upon a small museum book of Japanese paintings that belonged to my mother z”l. The covered showed an egret (at first, I thought it was a stork — I need to improve my birdwatching skills) bathing in a body of water. Actually, there are two egrets in the scene. I just focused on the right side. The reeds kind of look as how I would imagine greens growing next to the Nile might look. And my friend later told me indeed egrets are found in Egypt.

When I do biblical art, I recently started adding a snippet from a pasuk (a phrase of Torah) to the side of the art. Here is another version of this painting, one that cites the plague of blood:

Parshat Vaera, Shmot 7:21 “and the blood was throughout all the land of Egypt.”

Quotes from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1970 Nobel Lecture

Who was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn? Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918 in Kislovodsk, Russia. In 1945 he was arrested for criticising Stalin in private correspondence and sentenced to an eight-year term in a labour camp, to be followed by permanent internal exile. The experience of the camps provided him with raw material for One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, which he was permitted to publish in 1962. In 1970 he gave a lecture upon receiving the Nobel prize, and the main topic was art.

Not everything can be named. Some things draw us beyond words. Art can warm even a chilled and sunless soul to an exalted experience. Through art we occasionally receive–indistinctly, briefly–revelations the likes of which cannot be achieved by rational thought.

Later in the lecture:

But who will reconcile these scales of values and how? Who is going to give mankind a single system of evaluation for evil deeds and for good ones, for unbearable things and for tolerable ones–as we differentiate them today? Who will elucidate for mankind what really is burdensome and unbearable and merely chafes the skin due to its proximity? Who will direct anger toward that which is more fearsome rather than toward that which is closer at hand? Who could convey this understanding across the barriers of his own human experience? Who could impress upon a sluggish and obstinate human being someone else’s far off sorrows and joys, who could give him an insight into magnitude of events and into delusions which he has never himself experienced? Propaganda, coercion, and scientific proof are equally powerless here. But fortunately there does exist a means to this end in the world! It is art. It is literature.

Source: The Solzhenitsyn Reader, edited by Edward E. Ericson, Jr. and Daniel J. Mahoney

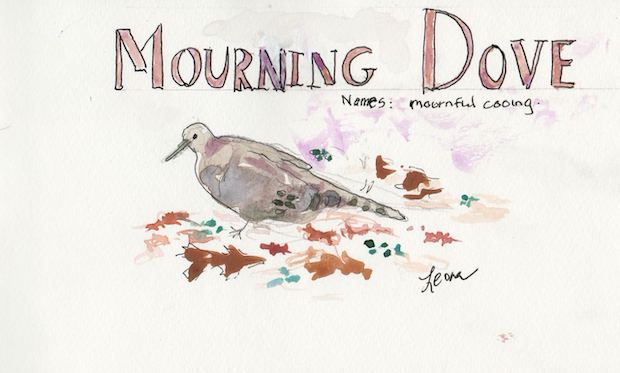

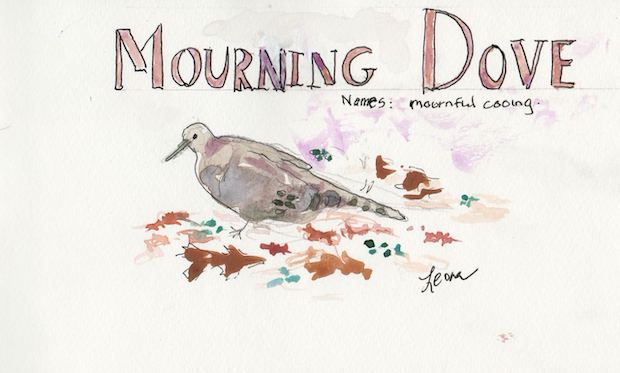

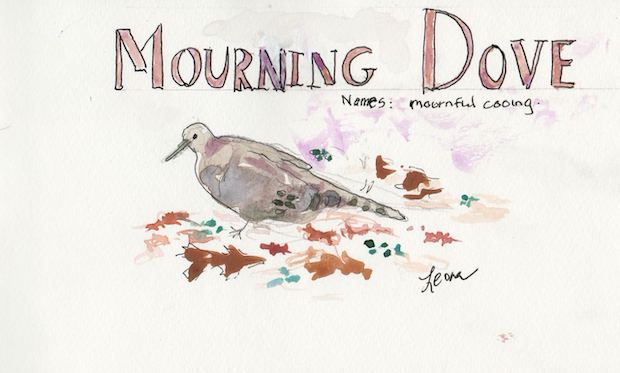

This week a mourning dove was wandering about my front yard. Instead of grabbing a camera and photographing the bird, I took my watercolor sketchpad (Travelogue Artist Watercolor Journal) and used a pencil and pen to draw the bird. I took it back in the house, added a little watercolor to the bird, went back out again to examine the mourning dove carefully. Yes, it did have those spots toward the tail. Yes, they were a shade of darkish gray. Yes, the beak was also darkish gray. Later I looked in my Birds of New Jersey Field Guide by Stan Tekiela and learned more:

Name comes from its mournful cooing. A ground feeder, bobbing its head as it walks. One of the few birds to drink without lifting head.

The one in my yard seemed to have a longer beak than the one pictured in the book.Also, I did not see the bright color in the head that Stan Tekiela showed in his photo. Adding a bit of lavender did seem to match the bird that I saw. However, as an artist one could also say using lavender was artistic license for either shadow or for gradations of hue or saturations.

Do you see birds in your yard? Do see distinguishing marks on the birds, whether color, spots or types of feathers?

A book review of The Man Who Never Stopped Sleeping by Aharon Appelfeld

This review explores important themes of the book, such as sleep, names, separation, literary explorations within a book, connections to the past, and healing.

Basic plot: The main character along with a group of teenage boys is a Holocaust survivor. He and this group have lost their parents and presumably their entire extended families, murdered in the Holocaust. The book follows the main character as he first joins the group in Naples and later they travel as a group by boat to the land of Israel (it was not yet the State of Israel). He works in the fields, and then when the fighting starts, he is almost immediately wounded. The story weaves from the realities the young man faces to his dreams and subconscious connections to his parents and other people of his childhood. The book also gives a glimpses of how the other boys cope (or not) as well.

Sleep: In Appelfeld’s book, why does the title imply that the main character never stops sleeping? In the beginning of the book, fellow refugees must carry him fast asleep from place to place. A few chapters into the book, he seems quite awake. Perhaps the reference is to character’s emotional world. He seems to prefer to connect to the world of his childhood. By the end of the book, he is spending more time in his dreams and his mind than he is interacting with people that are really alive in his world. By the end of the book, his dead mother seems more real in his dreams than the people of Tel Aviv, where he then lives.

What’s in a name? An important theme in the book is a name. The boys indeed many of the Holocaust survivors are urged to change their European names, the names their (now dead) parents had given them, to Hebrew names. Ephraim, their leader, didn’t have to change his. He was born in the Land with a Hebrew name. One nurse that he meets emphatically did *not* give up her name, and the main character regrets that he did not have her strength. There is one boy in their group who does not give up his name – tragically, he has way too much pain in general; he makes a deadly choice.

Some of the best parts of the book are references to literary text and text of the Bible. As a patient convalescing, the author is introduced to Agnon. He talks about a connection to Kafka through his father; he remembers his father bringing home short stories by a little known author named Kafka. It makes sense that he connects to Agnon in his real and present world, the land where Agnon wrote his stories. And Kafka is part of the tragic Jewish European experience, a foreboding of the crazy, evil world of the Holocaust. He learns Bible through a character named Slobotsky, described as a genius when he lived in Berlin. Slobotsky gives a lesson on prayer: voiced prayer and the voiceless prayer of Hannah. The reaction of one of the boys: Why are we studying the Bible and not biology?

Separation: in the normal course of life, a child is supposed to eventually separate from his parents. But if a child is emotionally very attached to parents and the parents are “yanked†away (murdered brutally), it can be hard for the child, even as an adult, to ever separate.

“Where have you been, father?” I asked, struggling to breathe. “Here,” he said, in a voice I knew in all its timbres.” “But they drove us out and scattered us.” “You’re mistaken, my dear. We were together, we were always together, even when we momentarily parted. The camps existed and then disappeared, but we remained together.” That was Father. Time had not stained his face. p. 61-62

Connection to the past: there is a character who shows up off and on in the book, Dr. Weingarten. Dr. Weingarten is the only person who is familiar with his family, the only connection to his past who is still alive. We learn about the main character’s parents through Dr. Weingarten. There is another older character who seemed to know of his grandfather. It is a struggle to connect to his childhood. He often fears losing his childhood language, while at the same time he struggles to improve his Hebrew by copying biblical texts (and Agnon text as well).

Healing, Doctors and Names: Why is the doctor who operates on him called Dr. Winter? What is the symbolism of the name? The other doctors are discouraging. Only Dr. Winter brings tempered hope. Maybe he only can offer physical healing. The emotional fractures remain. Maybe the emotional part must treated by the main character himself, as he struggles to become the writer his dead father wanted to be.

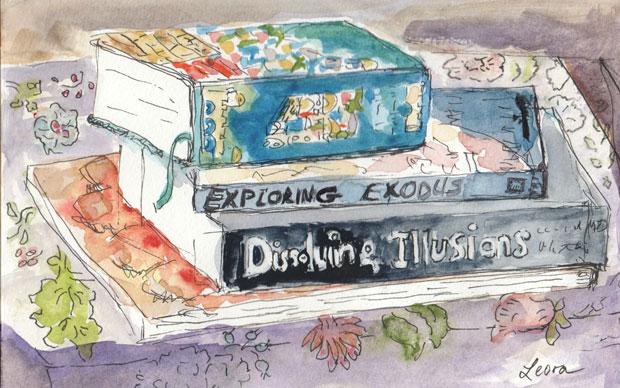

Have you ever heard someone speak, and felt you have become part of history? Last week I had the pleasure of hearing Lucienne Carasso, author of Growing Up Jewish in Alexandria: The Story of a Sephardic Family’s Exodus from Egypt tell us about her book at Congregation Etz Ahaim in Highland Park, New Jersey. After the Tahrir Square protests in Egypt (2011), she decided if everyone was talking about Egypt, it was time to tell her story, too. Others have written about growing Jewish in Egypt (see, for example, review of The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit), but Lucienne Carasso had her own story to tell. Indeed, she uses the book to trace her own family’s history, back to Salonika and even further back to Spain; she hypothesizes some of her family may have come from Catalonia.

A little about Alexandria and its history: Alexandria was founded in 331 BCE by Alexander the Great. He chose the spot on the Mediterranean because it had a natural harbor, fresh water and favorable weather. Many people, not only Jews, came to Alexandria in the later 19th century and early 20th century because of new economic opportunities, especially in cotton (rice and onions are two other major agricultural products of Egypt). Alexandria became a cosmopolitan city, with Greeks, Italians, Jews, Armenians and others.

Life was fun for Lucienne as a child growing up in Alexandria. She was loved by extended family, enjoyed gardens, beaches, pastry shops and the movies. Then one day in November 1956 her father is arrested. This is one year after Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in Egypt. Her whole world changes. Jewish businesses are taken away by the government, and most Jewish families leave, only with a limited amount of possessions. Her family stays a little longer, as her two grandmothers are still alive, and it takes a while for her father to liquidate what remains of his businesses. She goes from having many playmates to being alone with a few of her adult relatives.

One aspect of the book that I quite enjoyed was about Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish language that was spoken by the Jews of Spain before the expulsion in 1492. Spanish Jews continued to speak Ladino when they moved to cities like Salonika and Istanbul. Indeed, some of my adult friends at Congregation Etz Ahaim spoke Ladino as children. Lucienne’s grandmothers both spoke Ladino to her, reciting Ladino proverbs. Her Nona Sol (maternal grandmother) used to call her “morenica y savrosica” – loosely translated as “dark-haired and flavorful little girl.” Lucienne and her family spoke French at home and learned French at school, but for expressing deep feelings, Ladino was used. In reference to the expulsion of Jews from Spain and the invitation from sultan of the Ottoman Empire for Jews to come, she quotes her father’s expression: “Donde una puerta se cierra, otra se abre” – when one door closes, another one opens.

Her writings on food are sprinkled throughout the book. She loved ice cream and describes enjoying it in restaurants and making it at home. Her family is thrilled to discover in New York you can buy ice cream in the store and store it in your freezer. Sephardic pastries make a showing – women in her family specialize in roscas, ghorayebas and menanas (if anyone knows more about these, feel free to leave a comment). Her family does not keep kosher; the religious members of her family were a few generations back. When she is feeling depressed after her father is arrested and school is stopped for her, she writes about indulging a little too much in rich foods as comfort.

What is freedom? When her family spends time in Italy after being forced to leave Egypt, one of the movies they have the opportunity to see is Exodus. In Egypt one cannot say the word Israel or talk at all about Zionism. The teachers in her school after the rise of Nasser said terrible things about Israelis and Jews. Lucienne speaks of her and her parents’ reaction to an Exodus scene:

“When they sang out loud ‘Hatikva,’ which we used to whisper in Alexandria, my parents and I burst into tears. We were so moved. I knew then we were really free.

Another example of freedom is shown when Lucienne becomes a student in high school in New York City. Her English teacher is giving his interpretation of a novel. A student raises her hand and says she disagrees. Lucienne’s reaction:

“I almost fell over. I could not believe my ears. In the French educational system, one never challenges the teacher. The teacher is the “Authority” with a capital “A.” That day, I learned the meaning of democracy and free speech. A student could be entitled to her opinion as much as the teacher. Wow – what an idea!”

Lucienne Carasso reads from her book at Congregation Etz Ahaim, Highland Park, New Jersey

One of the selections she read from the book at her speech at Congregation Etz Ahaim was her response to the question of her teacher – “Who is the hero of the Egyptian Revolution?” She learns quickly that she should respond Gamal Abdel Nasser. She did not have to believe her teachers, but she had to spit out back whatever they were teaching.

Several members of Congregation Etz Ahaim grew up in Alexandria or Cairo, Egypt. We had two women at our table who had spent their childhoods in Alexandria.

Lucienne enjoyed the movies as a teen, but for her notes on the movies I will recommend you read the book. If you enjoy history and biography or want to learn about other cultures or life under totalitarian societies, Growing Up Jewish in Alexandria: The Story of a Sephardic Family’s Exodus from Egypt is a rewarding read.

You might think a book called Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust would make you incredibly sad. Perhaps. Well, most probably. But perhaps also it will give strength, hope, inspiration. In the forward to the book, Yaffa Eliach explains how she gathered these tales. They are based on interviews and oral histories, compiled with the help of her Brooklyn College students. She begins by relating the history of Hasidism, a movement founded by the Baal Shem Tov (1700 – 1760). From the foreword: “The main themes of Hasidic Tales are love of humanity, optimism and a boundless belief in God and the goodness of mankind.” One can see why this form of tale could be helpful in relating the horrors of horrors of the Holocaust.

“You can’t fool me there ain’t no Sanity Clause.” That phrase from the Marx Brothers movie came to mind as I was reading the book. But instead, I thought, “You can’t fool me, there ain’t no happy ending!” When I first started reading the tales, I found them so unbearably sad, I had to stop reading the book for a while. But when I picked it up again, the belief in humanity was like a spark that compelled me to read further.

For example, there is the story about Rabbi Spira who always used to say hello or good morning to everyone he passed, including Herr Muller. When Rabbi Spira was taken to Auschwitz, and it was his turn to be in the selection of right or left, he looked up, and there was Herr Muller. The rabbi was sent to the right – to life. Many years later, Rabbi Spira relates this conclusion: “This is the power of a good morning greeting. A man must always greet his fellow man.”

Another story that touched me was one of Moshe Dovid and his father, a Hasidic rebbe. Moshe Dovid was used to following his father’s advice; so when his father told him separate in order to survive, he did. He later discovered his father’s advice incorrect, and he went back to him, saying his advice did not work. His father sadly explained that these were very unusual times, and he could no longer be the one to give the sage advice. The rebbe said he is like the leader ram of the herd that a shepherd in his anger has blinded. Each person had to decide on his own and trust his own instinct. Moshe Dovid was able to survive the war.

Several survivors talk about a deceased father or a mother or a rebbe coming to them in a dream. And this person in the dream would encourage the person still alive to survive and give the person meaning.

A fascinating tale is that of Zvi, who survives a shooting by falling into the grave a split second before the volley of fire hits him. He climbs out at night and looks for a Christian home that will shelter him. All send him away. Then he comes up with a plan – I won’t tell you who he pretends to be – you will have to read the story yourself.

Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust by Yaffa Eliach (written in 1981) should be rated as a classic in Holocaust literature. And here is the conclusion to the foreword, a quote from Bertolt Brecht: “The imagination is the only truth.”

This writing desk used to belong to my mother z”l. My husband expressed some satisfaction when I he saw me use it one day as an actual desk. I was using it to address a few bat-mitzvah invitations. Which brings me to my next topic: blogging breaks. It seems that Purim stretched into pre-Pesach cleaning which then became Pesach and then a few busy work deadlines. Without strong intention I took a bit of a blogging break. I suppose ideally one should say, hello, I am taking a blogging break, but usually life is too busy for that sort of thing. Until after the bat-mitzvah I should just not plan on blogging very much. When it gets really hot in July, then I can get into the blogging swing again (I hate the heat and prefer air conditioning).

About the desk: my mother used to use it to write letters and organize recipes. I wish I had her collection of recipes – I assume it got thrown out at some point. The desk is quite fragile and is falling apart in pieces. I told the movers (we moved it from my father’s apartment after he died) that this was the last time the desk was moving (they didn’t want me to blame them for the broken pieces, and I don’t). But if my daughter gets attached to it, maybe it will move again. Who knows.

I was planning to write a post called Burning Bread and other Pesach Adventures. I have a great photo to go with that post. I’ll keep it in mind – maybe someday it will show up. My daughter was the Genie in a recent Highland Park Recreation production of Aladdin – if I had the energy, time and ideas, I might have posted about that. She was hilarious. Catch the next show on July 4th in Donaldson Park – no idea what that production will be.

I wish I were back doing watercolors – but too much else to do right now. Maybe in the summer? We’ve been having a gorgeous spring – it is quite therapeutic to go for a walk.

I highly recommend the book Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation by Yossi Klein Halevi. I would write a review, but I returned the book to my brother-in-law. I will just say this: it’s hard enough to write a biography of one person. Yossi Klein Halevi portrays quite a few varied people in this easy-to-read and engaging book.

Elsewhere in the Blogosphere

Over to You, Dear Reader

How do you handle needed blogging breaks? Is there anything in particular you might say to your audience? Have you ever gotten attached to an old piece of furniture?

Holocaust books can range from only brushes the surface to difficult to read to powerfully upsetting. There was one book I read in part and never finished because I found it so upsetting. In that book, everyone Jewish died (each a gruesome, slow death) – the narrator himself was a prisoner in the camp but not Jewish. Then there are books that seem to suggest if only we all were nice, such horrible things would not happen (except only nice people read those books – mostly drivel to me).

Out of the Depths: The Story of a Child of Buchenwald Who Returned Home at Last by Israel Meir Lau we get an autobiography with hope, perspective, respect for many different kinds of people and a story of a boy who loses his parents and much of his family but succeeds, succeeds in his own life and in touching many others. Rabbi Lau is imprisoned in Buchenwald as a young boy – most children his age are killed right away, but his brother, a Russian man and others manage to help him survive. At one point he is getting food to his brother Naphtali, because he is in the non-Jewish part of the camp where there are more rations, and his brother is among the Jews who get little. Because of his brother and his brother’s promise to his father, the two make it to pre-State of Israel Palestine and are reunited with an uncle and a half brother.

One cautionary remark about this book: in some ways it is divided into two parts. My 11th grade son had to read this book for school last year. He found the first part, where little Lulek (Rabbi Lau’s childhood nickname) survives the Holocaust, to be quite interesting. The rest of the book he found more difficult to read. Indeed, we follow Rabbi Lau around the planet where he visits the Lubavitcher Rebbe in Brooklyn, Fidel Castro in Cuba, King Hussein of Jordan and Pope John Paul II. As the narrative tends to jump around a bit, it is not always easy to move with it, but I found much of what he had to say of interest. For example, I did not know he was so close to Prime Minister Rabin. Sometimes he gives his divrei Torah (words of Torah) in detail, and you wonder if the person to whom he is speaking understands what he is saying.

This division of the book reminds me of the last book I finished: An American Bride in Kabul by Phyllis Chesler. Like Lau’s book, much of the exciting tale happens in the first part of the book, and the rest of the book is explanatory narrative and less dramatic parts of her life, like conversations with her ex-husband forty years later. My apologies to Phyllis Chesler for not writing a full review right now (that’s the problem with taking out brand new library books – you can’t keep renewing them). A jewel of Chesler’s book is a short history of the Jews of Afghanistan. Another remark that relates the story of Phyllis Chesler with that of Rabbi Lau: although she says she comes from an Orthodox Jewish family, it is clear she had very little Jewish education. In contrast, Rabbi Lau came from a long line of rabbis, and his brothers and uncle made sure he got a strong Jewish education in Israel. He also was clearly a gifted student – he jumped from first to fifth grade in one year. Would she have had such a strong attachment to an Muslim Afghan man if she had a stronger education and heritage? Who knows.

One of the most revealing parts of Out of the Depths were the early years in Israel when no one talked about the Holocaust, not survivors or native Israelis. There was some kind of shame attached; indeed, children were taught the Jews went like sheep. In retrospect, one can argue with this statement, but it helps to understand how Holocaust survivors were not given the opportunity in those years to work through the grief, the anger, and all the other feelings. When Eichmann came to trial in 1962, finally, the dialogue about the Holocaust began.

There was one character in the book for whom I felt bad and didn’t really get Rabbi Lau’s reaction to him: the Yiddish poet Itzik Manger. Rabbi Lau comes to visit Manger as he lies ill; Manger compared himself to Noah and how he got drunk after the flood. Rabbi Lau’s comment to the reader is “Although I understand Itzik Manger, I choose to identify with those who suffered immensely during the war but who opted to lead their lives in a vastly different mode.” I am not convinced he really does understand Itzik Manger. This is not to say one should tolerate alcoholism, but underneath that choice to drink alcohol was clearly a lot of depression and grief. I can accept how one can be in such a state having lost one’s whole world. Rabbi Lau claims he understands, but I didn’t really feel that. Perhaps with the right kind of professional understanding and help, Itzik Manger could have had some more healing in his life.

On the other hand, I was in awe of his conversations with the Pope, Fidel Castro and King Hussein. For example, Fidel Castro asks Rabbi Lau a thought provoking question:

Here in Cuba, a child of eight growing up without parents, and especially without knowing the language, will turn into a juvenile deliquent…But you came to Israel barefoot and penniless, and today you are like the Jews’ pope…How did a boy from the streets, who started out with nothing, get chosen to be the senior religious representative of the country?

And then Rabbi Lau, after initially surprised by the question, talks about his heritage of a long line of rabbis, and how his father left a spoken last will and testament with his older brother to take care of his younger brother, and how his uncle took care of him when he finally arrived. He spoke of his teachers in yeshiva and of his tutelage under his father-in-law, Rabbi Frankl. He felt even though he lost his parents, in many ways they stayed with him.

I was impressed with Rabbi Lau’s own self reflection – he was able to note that separations are painfully difficult for him, because of his early separations from his mother and his brother (he was reunited with his brother). He said even a simple goodbye party when leaving a position did not feel good to him.

If you like autobiographies, this is well-worth reading. If you would like to read about a Holocaust survivor’s story, this one is more upbeat than many others. I also learned a bit about the role of the chief rabbi in Israel. The book certainly gave us a rabbi who is a well-rounded person and able to connect to many.

Welcome, Adam! Readers, enjoy this interview with Adam Gustavson, illustrator of the award-winning children’s book Hannah’s Way; the interview is part of the Sydney Book Awards Blog Tour.

Description of the book: After Papa loses his job during the Depression, Hannah’s family moves to rural Minnesota, where she is the only Jewish child in her class. When her teacher tries to arrange carpools for a Saturday class picnic, Hannah is upset. Her Jewish family is observant, and she knows she cannot ride on the Sabbath. What will she do? A lovely story of friendship and community.

How did you decide how Hannah should appear? her family? the scenery? Did you do research on the period’s clothing and style?

That a good question. Before I even picked up a pencil, I immersed myself in images of people from the 1930s. I looked at as many ancestry web sites as I could and thumbed through books of costumes and period photography. I also dug as far into Orthodox Judaism as I could, just trying to make sure the family in the book didn’t fly in the face of some hidden clause from Leviticus that I didn’t know about.

I looked at lots of sale items on ebay, trying to keep in mind that the era a story takes place in isn’t really the era of the stuff in it, it’s the cut-off date for said stuff. The couches, the lamps, the architecture, all of that has to predate the story. And if someone in the story is dressed in hand-me-downs, well, now we’re looking at fashion from the late ’20s…

As far as the characters themselves, I rely as much as I can on instinct. Granted, I research hairdos and ethnic bone structure and think about people I know or have known that fit a temperament or demographic, but one of the really important aspects of being able to draw the same person, active and emoting for 32 pages, is to really believe that they’re the right person for the job.

How did you team up with the author, Linda Glaser?

Illustrating books is a sort of funny thing; the whole affair is orchestrated by the publisher, so as it was Joni Sussman at Kar-Ben who contacted me about illustrating the Hannah’s Way.

What inspired you to become an artist?

I’ve always drawn; my mother was an artist when I was growing up, and my brothers and I drew like most other kids would play ball. It was a big part of how we played together. My father, an engineer, used to come home with art supplies he’d picked up for us on his way home from work. I grew up in the only household for miles and miles where a crisis consisted of my mother trying to find out just who took her kneaded eraser.

When I went to college, the toss up for me was between becoming an artist or becoming a musician. So again, I was pretty much the only person I knew who went into art because it was the more practical choice.

I love the illustrations you did of commuters on a train

(see http://adamgustavson.blogspot.com/2012/08/the-summer-in-mostly-mass-transit.html).

What advice would you give someone who wants to improve his/her drawing skills?

There are two things I’d say; the first and foremost is to draw everything all the time. The way I put it to a student recently was that if what you really want to draw is Spiderman, at some point you’ll have to figure out what kind of furniture Aunt May has in her living room. A big part of making art is experiential, which is to say you don’t really know what something looks like until you try to draw it, and really explore it in your drawing.

Another important aspect is to be influenced by things that aren’t specifically what you want to do. This goes for technique, subject matter, and high falutin’ compositional stuff. A high profile example of this idea at work is in Van Gogh’s love of Japanese woodcuts, and the way that it translated into how he used paint, but it exists to some degree almost everywhere.

What projects are you working on now?

I’ve just finished a really sizable project for Holt’s Christy Ottaviano Books imprint, called “Rock and Roll Highway: The Robbie Robertson Story,” written about the co-founder of the Band by his son, Sebastian Robertson. It involved over thirty oil paintings and real life protagonist that had to age about 30 years in the course of the narrative, which was a bit of a challenge.

You seem like you have worked on many books and illustration projects – which were your favorites?

My two all time favorites have been Leslie Kimmelman’s “Mind Your Manners, Alice Roosevelt!” and Bill Harley’s “Lost and Found,” the latter of which just came out this past fall. From a concept, design and storytelling perspective (the Alice Roosevelt book was very research heavy, to boot), both projects had a lot of freedom involved and called for a really dynamic range of images. Any project that calls specifically for a 1904 Studebaker or leaves room for a stuffed flying badger can’t be all that bad.

Can you tell us a little about the zombie project? How did you get involved in that one?

(see http://adamgustavson.blogspot.com/2012/11/what-do-pete-mitchell-bryan-ballinger.html)

I was invited by illustrator Bryan Ballinger, a friend of Pete Mitchell, a cartoonist and the singer for the band No More Kings, to participate in an anthology of zombie comics, which was an impossible thing to say no to. The idea as I understood it was to have the book available for release at the same time as the band’s latest album.

I batted around several ideas over the course several months before writing up a conversation between two undead companions, one of whom was having an existential crisis.

What is the hardest part of illustrating a book? What part is the most rewarding?

The hardest part is not the “getting started” part, having 32-40 blank pages staring back from a computer layout, though sometimes it seems like it could be.

The hardest part for me is the part I call Page 28 Syndrome: being in the home stretch of something that has been lived with for six to nine months, and putting finishing touches on that scene that every book has that happens right after the conflict is resolved but the story hasn’t ended yet. It feels like 101st mile of a 100 mile run, where instead of running you’re just consciously lifting your knees to get to the end, and trying not to trip. That right there, that’s the hardest part.

The most rewarding part for me was always the moment before a project was shipped off the the publisher, looking at everything spread out on the floor in order.

But truthfully, grade school appearances are really the thing that does it now. The whole process of making books can be so isolating, so much about high minded professional practices done in a cave, that it’s not hard to lose sight of who these things are really for. Wandering around among actual humans ‹ preferably short ones ‹ with a book is really my favorite part.

And I think it’s a reminder of why that page 28 syndrome thing is important to get through. There are plenty of examples out in the world where adults cut corners or cheap out on things for children because they think their target audience won’t notice. And often they’re right. But that doesn’t really matter, does it? Children deserve better things than that, whether they’ll recognize it or not.

The worst thing we can do as people in the creative class is willfully accustom our audiences to mediocrity.

• • •

To learn more about Adam Gustavson, you can visit http://adamgustavson.blogspot.com/. About the book Hannah’s Way, see: http://www.karben.com/Hannahs-Way-Paperback_p_502.html